What Really Helps After Baby? My Science-Backed Recovery Journey

Bringing a baby into the world is beautiful, but recovering afterward? That part rarely gets the real talk it deserves. I used to think rest alone would heal everything—turns out, science says otherwise. From pelvic floor puzzles to energy crashes, postpartum recovery is more complex than we’re told. This is not about bouncing back fast, but healing right. Let me walk you through what actually works—based on research, real changes, and lessons I wish I’d known earlier.

Understanding Postpartum Recovery: More Than Just Resting Up

Postpartum recovery refers to the physical, hormonal, and emotional adjustments a woman's body undergoes after childbirth. While many expect to simply “rest and recover,” the reality is far more intricate. The postpartum period is not a passive phase but an active process of healing that can last months—or even years. It begins immediately after delivery and unfolds in distinct stages: the immediate postpartum phase (0–6 weeks), the mid-term recovery window (6 weeks–6 months), and long-term healing (6+ months and beyond). Each stage brings unique challenges and milestones, shaped by individual factors such as mode of delivery, pre-pregnancy health, and access to support.

One of the most persistent myths is the idea of “bouncing back” quickly after birth. Media portrayals often show new mothers resuming intense workouts or fitting into pre-pregnancy clothes within weeks. However, biological evidence contradicts this expectation. The body undergoes profound changes during pregnancy—ligaments loosen, organs shift, and muscles stretch. Healing from these transformations takes time. For example, the uterus, which expands to accommodate a growing baby, requires about six weeks to return to its pre-pregnancy size. Yet even then, internal healing continues beneath the surface.

The type of delivery significantly influences recovery. Women who experience vaginal birth may face perineal soreness, tearing, or episiotomy healing, while those who undergo cesarean sections are recovering from major abdominal surgery. Both paths require careful attention, yet each comes with different timelines and physical demands. Additionally, hormonal fluctuations play a central role. Within days of delivery, estrogen and progesterone levels plummet, contributing to mood shifts and fatigue. Emotional well-being is not separate from physical recovery—it is deeply intertwined.

Every woman’s journey is unique. Genetics, nutrition, mental health history, and social support all shape how someone heals. Some may feel stronger by eight weeks; others may need more time to regain stamina and stability. Recognizing this variability is essential. Rather than comparing oneself to others or striving for unrealistic benchmarks, the focus should be on listening to the body, honoring its needs, and supporting it with informed care. Recovery is not a race—it’s a personal process that deserves patience and compassion.

The Core Fix: Rebuilding Abdominal and Pelvic Floor Strength

One of the most overlooked aspects of postpartum healing is core rehabilitation, particularly the restoration of abdominal and pelvic floor strength. During pregnancy, the growing uterus places increasing pressure on the abdominal wall, often leading to a condition known as diastasis recti—the separation of the rectus abdominis muscles along the midline. This is not a rare occurrence; studies suggest that up to two-thirds of pregnant women develop some degree of abdominal separation by the third trimester. While mild cases may resolve on their own, moderate to severe diastasis can persist if not properly addressed, leading to lower back pain, poor posture, and reduced core stability.

Equally important is the pelvic floor—a group of muscles that support the bladder, uterus, and bowels. These muscles stretch significantly during childbirth and can become weakened or damaged. Pelvic floor dysfunction may result in urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, or discomfort during daily activities. Despite how common these issues are, they are often dismissed as “normal” after birth. However, science confirms that while some degree of change is expected, persistent symptoms should not be ignored. Both diastasis recti and pelvic floor weakness are treatable with targeted, evidence-based approaches.

The key to effective recovery lies in proper muscle activation, not intensity. Early postpartum exercise should focus on re-establishing neuromuscular control—the brain’s ability to communicate with and engage specific muscles. The transverse abdominis, the deepest layer of the abdominal wall, plays a crucial role in stabilizing the core. Gentle bracing techniques, such as drawing the lower abdomen inward while breathing normally, help retrain this muscle without straining the healing tissues. Similarly, Kegel exercises—rhythmic contractions of the pelvic floor—can improve muscle tone and bladder control. Research shows that women who begin pelvic floor muscle training early postpartum are significantly less likely to develop long-term incontinence.

Timing is critical. Most healthcare providers recommend waiting until cleared at the six-week postpartum checkup before beginning structured exercise. However, gentle activation can often begin sooner under professional guidance. What must be avoided, especially in the first 12 weeks, are high-pressure movements like crunches, planks, or heavy lifting, which can worsen diastasis or strain healing tissues. Instead, focus should be on mindful engagement, proper breathing, and gradual progression. Physical therapists specializing in women’s health can provide personalized assessments and tailored exercise plans, ensuring safe and effective recovery.

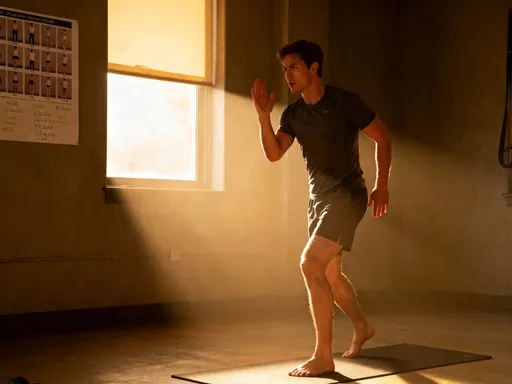

Movement That Heals: The Role of Early, Safe Physical Activity

Contrary to the belief that new mothers should remain sedentary after birth, science supports the benefits of early, gentle movement. Physical activity in the postpartum period is not about burning calories or losing weight—it’s about restoring circulation, supporting tissue repair, and improving mental well-being. Even short walks around the house or neighborhood can enhance blood flow, reduce the risk of blood clots, and help regulate mood through the release of endorphins. Movement also aids in preventing constipation, a common issue due to hormonal changes and pain medications used during delivery.

The progression of physical activity should follow a structured, research-backed approach. The initial phase focuses on mobility: standing, walking, and practicing proper posture. For women recovering from vaginal birth, short walks can often begin within the first few days, provided there are no complications. Cesarean section patients may need more time, typically starting with assisted standing and slow walking by the third or fourth day. The goal is not distance or speed, but consistency and comfort. As healing progresses, the focus shifts to posture training—learning to align the spine, engage the core, and avoid compensatory movements that can lead to pain.

By six to eight weeks postpartum, many women can begin light strength training, assuming they have medical clearance. This includes exercises like glute bridges, seated leg lifts, and supported squats, all of which build functional strength without excessive strain. Resistance bands and bodyweight movements are ideal during this phase. The transition to more intense workouts should be gradual, with attention to how the body responds. Any sign of pelvic pressure, urinary leakage, or pain should signal a need to modify or pause activity.

It’s important to recognize that recovery timelines differ based on delivery method. Cesarean recovery involves healing from a surgical incision, which requires careful management of intra-abdominal pressure. Women who have had C-sections are often advised to avoid lifting anything heavier than their baby for the first six weeks. Vaginal birth, while less invasive, still involves significant tissue stretching and potential trauma. Both paths demand respect for the body’s limits. The message is clear: movement supports healing, but overexertion can delay it. Consistency, not intensity, is the foundation of a successful recovery.

Nutrition as Fuel: Supporting Healing from the Inside Out

While much attention is given to diet during pregnancy, nutritional needs remain elevated after childbirth—especially for breastfeeding mothers. The body is still in a state of repair, rebuilding tissues, restoring blood volume, and producing milk. Caloric needs increase by approximately 300–500 calories per day during lactation, but quality matters just as much as quantity. A balanced, nutrient-dense diet provides the building blocks for recovery, energy, and milk production. Yet many new mothers struggle to eat well due to fatigue, time constraints, and shifting priorities.

Key nutrients play specific roles in postpartum healing. Protein is essential for tissue repair and milk synthesis; good sources include lean meats, eggs, legumes, and dairy. Iron helps replenish blood lost during delivery and combats fatigue; red meat, spinach, lentils, and fortified cereals are valuable options. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts, support brain health and may help regulate mood—important given the hormonal shifts that occur postpartum. Fiber aids digestion and prevents constipation, a common issue due to slowed gut motility and pain medications. And hydration cannot be overstated: breast milk is about 87% water, and even mild dehydration can affect milk supply and energy levels.

Practical eating strategies can make a significant difference. Preparing simple, balanced meals in advance—such as oatmeal with fruit, grilled chicken with vegetables, or yogurt with nuts—can save time and reduce decision fatigue. Snack prep is equally valuable; keeping cut vegetables, hard-boiled eggs, or cheese sticks within easy reach encourages healthier choices. Eating small, frequent meals helps maintain steady blood sugar levels, preventing energy crashes and irritability. Pairing carbohydrates with protein or fat—like apple slices with peanut butter—slows glucose absorption and sustains energy.

Myths about postpartum nutrition can be misleading. The idea of “eating for two” persists, but after delivery, the focus should shift to nutrient quality, not excess calories. Similarly, attempts at rapid weight loss are discouraged, especially in the first three months. Extreme dieting can impair milk production, delay healing, and increase the risk of nutrient deficiencies. The body needs time to adjust. Gradual, sustainable changes—such as increasing vegetable intake, choosing whole grains, and reducing processed foods—are more effective and safer in the long term. Nutrition is not about restriction; it’s about nourishment.

Hormones and Healing: Why You Feel Emotionally Wobbly (And It’s Normal)

The emotional rollercoaster many new mothers experience is not a sign of weakness—it’s a biological reality. Within 48 hours of delivery, levels of estrogen and progesterone, which were extremely high during pregnancy, drop sharply to pre-pregnancy levels. This sudden hormonal withdrawal affects neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly serotonin and dopamine, which regulate mood, sleep, and motivation. At the same time, oxytocin—the “bonding hormone”—rises during breastfeeding and skin-to-skin contact, promoting attachment but also contributing to emotional sensitivity.

These hormonal shifts help explain why many women feel tearful, irritable, or overwhelmed in the first two weeks after birth—a condition commonly known as the “baby blues.” Up to 80% of new mothers experience some form of mood fluctuation during this time. Symptoms typically include mood swings, anxiety, and crying spells, but they are temporary and resolve on their own. However, when these feelings persist beyond two weeks, intensify, or interfere with daily functioning, they may indicate postpartum depression or anxiety, which affect about 1 in 7 women and require professional support.

Differentiating between normal emotional adjustment and clinical conditions is crucial. The baby blues are brief and self-limiting, while postpartum mood disorders involve more severe symptoms such as persistent sadness, loss of interest in the baby, difficulty bonding, intrusive thoughts, or thoughts of self-harm. These are not character flaws or personal failures—they are medical conditions that respond well to treatment. Seeking help from a healthcare provider is not a sign of inadequacy; it is an act of strength and care for both mother and child.

Science-backed coping strategies can support emotional well-being. Prioritizing sleep, even in small increments, helps regulate mood and cognitive function. Social connection—with partners, family, or support groups—reduces isolation and provides emotional validation. Mindfulness practices, such as deep breathing, meditation, or gentle yoga, have been shown to lower cortisol levels and improve emotional resilience. These tools do not eliminate challenges, but they create space for healing and balance. Emotional recovery is not optional—it is a vital part of overall health.

Sleep, Stress, and Recovery: Breaking the Exhaustion Cycle

Sleep—or the lack of it—is one of the greatest challenges of early motherhood. Newborns feed and wake frequently, leading to fragmented, unpredictable sleep patterns. While this is normal, the cumulative effect on a mother’s body is profound. Chronic sleep disruption elevates cortisol, the primary stress hormone, which in turn increases inflammation and slows tissue healing. Studies show that sleep-deprived mothers have higher levels of inflammatory markers, which can delay recovery and contribute to fatigue, mood disturbances, and weakened immunity.

The impact of sleep loss extends beyond physical health. Cognitive functions such as memory, decision-making, and emotional regulation are impaired. Simple tasks feel more difficult, and patience wears thin. Yet many women feel pressure to “do it all,” leading to guilt when they cannot meet self-imposed or societal expectations. This cycle of exhaustion and stress undermines recovery and diminishes quality of life. Breaking this pattern requires realistic strategies and a shift in mindset.

One effective approach is nap syncing—aligning the mother’s rest periods with the baby’s sleep schedule. While not always possible, even 20–30 minutes of uninterrupted rest can improve alertness and mood. Partner involvement is also key; sharing nighttime feedings (if bottle-feeding expressed milk or formula) or handling diaper changes allows the mother to get longer stretches of sleep. Lowering household expectations—accepting that chores can wait and meals don’t need to be elaborate—reduces mental load and frees up energy for healing.

Self-compassion is perhaps the most important tool. Instead of measuring productivity, women should be encouraged to measure progress in healing, connection, and self-care. Rest is not laziness; it is a biological necessity. The body repairs itself during sleep, rebuilding muscle, balancing hormones, and consolidating memories. By reframing rest as an active part of recovery, rather than a luxury, mothers can give themselves permission to prioritize it. Healing cannot happen in a state of constant stress. Creating pockets of calm, even in a chaotic schedule, supports both physical and emotional well-being.

When to Seek Help: Knowing the Red Flags and Getting Support

While postpartum recovery is a natural process, certain symptoms should never be ignored. Persistent pain—whether abdominal, pelvic, or perineal—beyond the expected healing window may indicate an underlying issue such as infection, scar tissue complications, or nerve damage. Urinary or fecal incontinence that continues past six weeks is not normal and may require evaluation by a pelvic floor therapist. For women who had cesarean sections, signs of wound complications—such as redness, swelling, discharge, or fever—should prompt immediate medical attention.

Emotional health is equally important. While mood swings are common, symptoms of postpartum depression or anxiety—such as persistent sadness, hopelessness, loss of interest, or difficulty bonding with the baby—warrant professional support. Thoughts of harming oneself or the baby are medical emergencies and require urgent care. These conditions are not a reflection of character or parenting ability; they are treatable medical issues. Therapy, counseling, and in some cases medication, can be highly effective.

Regular follow-ups with healthcare providers are essential. The six-week postpartum visit is not just a formality—it’s an opportunity to assess physical healing, discuss concerns, and create a personalized care plan. Many women benefit from additional support, such as physical therapy for core or pelvic floor rehabilitation, lactation consultants for feeding challenges, or mental health professionals for emotional well-being. These services are not luxuries; they are vital components of comprehensive postpartum care.

Asking for help is not a sign of failure—it is a sign of wisdom. No one should have to navigate recovery alone. Whether it’s accepting a meal from a friend, joining a new mother’s group, or scheduling a therapy appointment, reaching out strengthens resilience. Healing is not a solitary journey. With the right support, women can move beyond survival mode and step into a place of strength, confidence, and renewed well-being.

Conclusion

Postpartum recovery isn’t a race or a performance—it’s a personal, science-informed journey of rebuilding. Healing takes time, attention, and the right tools. By combining research with real-life adjustments, women can move beyond survival mode and step into lasting strength. This isn’t about returning to who you were—it’s about becoming who you are now, fully supported and deeply understood.